Ahead of his evening talk The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi, Colin Thom of the Survey of London, introduces us to Robert Adam’s ambitious but ill-fated Adelphi project.

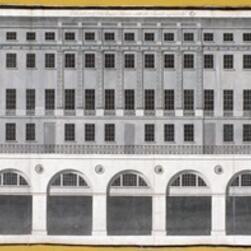

The Adam brothers’ concept at the Adelphi is immediately striking for its monumentality and ambition. Here was an unprecedented attempt to create a large and entirely new district of elegant housing, raised up by some extraordinary engineering on a series of vaulted warehouses above the River Thames, on what had been an unfashionable, run-down stretch of ground known as Durham Yard.

Robert Adam’s genius lay in his ability to take and adapt elements of antique architecture and create from them something that was uniquely his own. At the Adelphi, his principal inspiration was the ruined palace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian at Spalato (modern-day Split, in Croatia), which he surveyed in 1755 as part of his Grand Tour and which formed the subject of a detailed monograph, published by Adam in 1764.

Robert Adam had been captivated by the transformation of the palace at Split into a bustling modern city, as well as by its Roman remains. This aspect he reinterpreted for London as a mixed environment of houses of several sizes and classes arranged in a grid of streets, along with shops, coffee houses, a tavern, hotel, Coutts’ bank, and a new Adam-designed headquarters for the Royal Society of Arts on John Adam Street – all underpinned by the cavernous wharves and warehouses. There was something undeniably Picturesque about the Piranesian sequence of dark vaults beneath the urbane streets of housing above.

The Adelphi was begun at a time when Robert Adam’s star was in the ascendant. With a flourishing London practice and a succession of spectacular country house commissions behind him, he was Britain’s most fashionable architect; his Diocletian monograph had affirmed his status as a leading expert in the antique and in antique-derived Neoclassicism; and with his three brothers, John, James and William, he had recently established a London-based contracting and building supplies company – William Adam & Co. (which built the Adelphi) – echoing the family’s wide-ranging business interests in Scotland. But bold though the Adelphi was in its architecture and engineering, as a financial venture it was risky and impetuous, coming uncomfortably soon after the Adams had agreed with the Duke of Portland to build Portland Place on his estate at Marylebone - another ambitious town-planning commitment. They also had difficulty selling houses at their full valuation. Badly overstretched and with many properties unfinished, the Adams were forced to mortgage houses or sell them cheaply in order to raise capital to finish the development. Then a Scottish banking crash in the summer of 1772 tipped them to the verge of ruin. Though the sale of their assets by a private lottery saved them from bankruptcy, the brothers’ reputation had been tarnished, and they were never able to regain the heights of their earlier successes. The name Adelphi, chosen to immortalize the Adam ‘brotherhood’, also became a byword for over-reaching ambition.

The Adelphi survived in relatively good condition into the nineteenth century. In 1927 the Adelphi estate was sold at auction, and in 1936 many of the houses, including the great riverfront terrace and its underground vaults, were torn down and a new Art Deco Adelphi building (designed by Collcutt & Hamp) erected in their place.

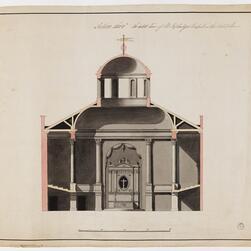

Today only a few runs of houses remain from the Adam development, in Robert Street, Adam Street and John Adam Street, including the beautifully proportioned Royal Society of Arts building, designed by Robert Adam.

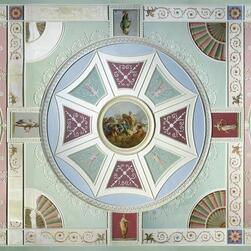

Other fragments survive here and there, particularly in the Victoria and Albert Museum, including the actor David Garrick’s front drawing-room ceiling - a friend of Adam who took a house at the centre of the Adelphi’s Royal Terrace - now incorporated into the British Galleries.

Book your place at Colin’s talk and enjoy a private view of the exhibition Robert Adam’s London and complimentary drink on arrival.

This is an extract from the Survey of London’s blog and is reposted with permission. Read the full post here.

Banner image ©Victoria and Albert Museum.