For the next in her series discussing Robert and James Adam’s work in London Dr Frances Sands will focus on their designs for funerary monuments in Westminster Abbey.

One of the most unstudied elements of Robert and James Adam’s oeuvre is their production of numerous funerary monuments and mausolea. Those most prominent in London are the Adam designs made for funerary monuments in Westminster Abbey.

Westminster Abbey is two hundred yards south of St James’s Park. Its early history is unclear, although there is evidence for the foundation of a Benedictine Monastery in the 960s. The abbey was rebuilt by Edward the Confessor, being consecrated in 1065. In 1139 Edward the Confessor was canonised, stimulating generations of royal patronage in devotion to his cult. The greatest example of this was the second rebuilding of the abbey from 1245 by Henry III. These works were finished in c.1532, with the completion of the Chantry Chapel, only for the monastery to be dissolved in 1540. However, the abbey itself was saved and transformed into the Cathedral of Westminster. During the Civil War Cromwell’s troops famously camped inside the abbey, causing considerable damage, resulting in a programme of restoration works in 1698-1723 to designs by Christopher Wren (1632-1723).

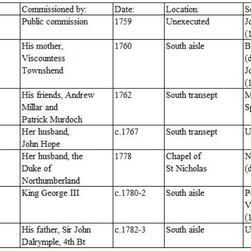

Doubtless prompted by the burials of Edward the Confessor and Henry III, the abbey became a popular mausoleum, and by the eighteenth century it was starting to get crowded. During the course of his career, Robert Adam made designs for seven funerary monuments for Westminster Abbey. These ranged from monuments to William Dalrymple, an eighteen-year-old midshipman killed in a clash with the French off the coast of Virginia, to Elizabeth Seymour Percy, 1st Duchess of Northumberland; or from Mary Hope, the wife of a prosperous London merchant, to the famous playwright James Thomson. Of these seven monuments, only one – Adam’s first design for the abbey – a monument to Major General James Wolfe of 1759, was not executed.

It is interesting to compare Adam’s unexecuted scheme for Wolfe, and that for his military colleague, Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Townshend, whose monument was designed by Adam only months later in 1760. Major-General James Wolfe (1727-59) was the eldest son of Lieutenant-General Edward Wolfe, while Lieutenant-Colonel Roger Townshend (1731-59), was the fifth son of the 3rd Viscount Townshend (later, Adam’s patron of Raynham Hall, Norfolk). Wolfe commanded the British forces in Canada and died in battle from three gunshot wounds five days before the surrender of Quebec (18 September 1759). He was hailed a national hero who had given his life for a triumphal victory. Townshend served in America, and died when he was hit by a cannon-ball at Ticonderoga, New York, fighting the French. Wolfe’s funerary monument in Westminster Abbey was a public commission, and Townshend’s was a personal tribute from his grieving mother.

As a public commission, the Wolfe monument design was opened as a competition, and alternative designs were put forward by William Chambers (1722-96), and Joseph Wilton (1722-1803). This was Adam’s first design for a funerary monument – surely lured by the fame that a public commission of this calibre would afford – and among other extant drawings there are six variant designs for the Wolfe monument. The final scheme shows a sarcophagus containing an inscription panel, flanked by columns ornamented with military trophies, and surmounted by the a relief panel showing Wolfe’s death scene, which in turn is flanked by antique military figures, and surmounted by military trophies attended by the figures of Victory and two defeated enemies, and the whole is set against a pyramid in relief. All of Adam’s schemes for the Wolfe monument make use of the death scene relief panel, but his designs were rejected in favour of one by Wilton. The composition was not to be entirely abandoned, however, as elements of the design reappeared a few months later when Adam was commissioned by Viscountess Townshend to design a monument to her son.

The Townshend monument is composed of two atlantes (male caryatids), flanking an inscription panel, and supporting a sarcophagus containing a death scene relief panel, and this is surmounted by military trophies, and set against a pyramid in relief. In Adam’s drawing the atlantes are shown as antique Roman slaves, but in execution they were Native American men (cultural group unknown), presumably referring to the location of Townshend’s death. They establish a pleasing stylistic contrast with the rest of the monument which is entirely classical. Indeed, it has been noted by John Fleming that the composition of a sarcophagus supported by caryatids or atlantes may have been inspired by Italian Renaissance monuments such as that for Pietro Lombardo at SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice; but it is also important to note that within Adam’s possession was a drawing of various Roman tombs by his tutor from the Grand Tour, Charles-Louis Clérisseau (1721-1820). Two of the tombs depicted in Clérisseau’s drawing comprise a strigilated casket supported by terms, being reminiscent of Adam’s design for the Townshend monument with its atlantes.

The most notable similarity between the Wolfe and Townshend monument designs can be seen in the central relief panel depicting the death scene. Here, like the Wolfe death scene, Townshend is shown reclining, surrounded by comrades, and with the battle continuing in the background. It is not known if Viscountess Townshend had been familiar with Adam’s design for the Wolfe monument, but it is likely as the Wolfe death scene includes another of her sons, George Townshend, to whom Wolfe is gesturing as his second-in-command. The marble relief panel for the Townshend monument is signed by the sculptor Joseph Eckstein (1735-1818), although a terracotta model for this was made by Luc- François Breton (1731-1800) in Rome. The monument itself is signed by Benjamin Carter (d.1795), but it is generally agreed that Eckstein was probably responsible for much of the work. The Townshend monument remains in situ in the south aisle of Westminster Abbey, although some of the heads of the figures in the death scene relief have been lost.

Dr Frances Sands, Catalogue Editor (Adam drawings project), has been working on a project to make 8,000 drawings from the Adam collection available to view Collections Online

As part of the Museum’s programme of digitization and improved access to collections the Adam drawings will also be amongst the 50,000 – 60,000 works of art, books and drawings, plus the Soane Archive to be transferred into the Collections Index+ Collections Management System (CMS) that will for the first time ever allow the Museum to store and sort records of all the items in the Museum’s collection. This has been made possible with thanks to funding from the HLF and an additional year’s funding by the Arts Council England’s Designation Development Fund for the collections information to become available to the public.